Boxwork

Wind Cave National Park. South Dakota. August 7, 2014.

Copyright © 2014 A. F. Litt, All Rights Reserved

Photo of the Day by A. F. Litt: November 13, 2014

On a snowy and icy day here in Oregon…

I find myself wishing I’d taken more than a single, blurry photo above ground in Wind Cave National Park. It was a beautiful evening when we were there and, above ground, the park is almost as nice as it is below, with a wild buffalo herd (one of only four “free roaming and genetically pure” herds remaining on public lands in the United States), prairie dog towns, and an old highway reminiscent of the HCRH.

But it was late in a long day that was far from done and we’d seen buffalo in Yellowstone, prairie dogs at Devils Tower, and rolling grasslands, well, everywhere… But it was our first cave of the trip, so my focus was somewhat subterranean here.

The park service really embraces the idea that this is two parks in one, one above ground, one below, and the nation’s seventh national park, founded in 1903 and the first to focus on a cave, “includes the largest remaining mixed-grass prairie in the United States.” (Wikipedia) It really is a wonderful place.

Earlier in the day, we’d been to Mt. Rushmore, wandered the museum at Crazy Horse, and then tried to tack on a trip to Jewel Cave National Monument, but by the time we arrived, the tours were done for the day. So we hauled ourselves rather quickly over to Wind Cave and managed to catch one of the last tours of the day. When we arrived, the light was just settling into the golden hour, it really was a great time for photos, but at the time I think these sorts of shots just felt a little redundant to me by this point in the trip.

Besides, as my oldest son often points out, sometimes its ok, even better, just to have the memories, and I know that sometimes I enjoy the sights a little bit better if I am not worried about taking pictures, so in this way, the lack of pictures is well worth the wonderful memories of the evening’s drive through the park.

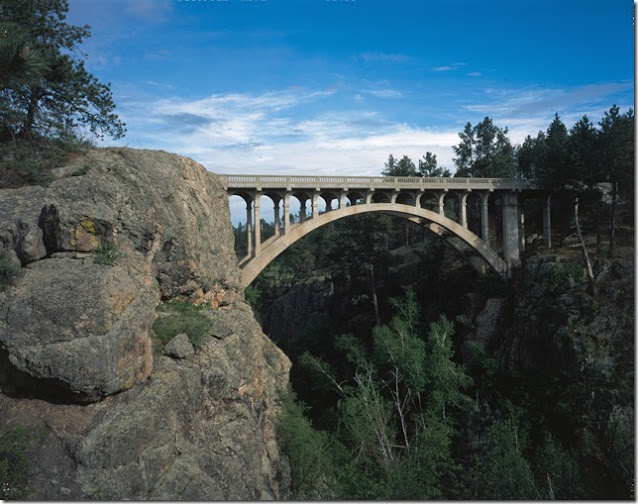

Beaver Creek Bridge in Wind Cave National Park

Underground, the 140 mile cave is currently the sixth longest known cave in the world, and is primarily known for the boxwork formations seen in today’s photo. The cave contains “approximately 95 percent of the world’s discovered boxwork formations.” (Wikipedia) It is also recognized “as the densest (most passage volume per cubic mile) cave system in the world.” (Wikipedia)

Some people suspect that Jewel Cave, currently the third longest known cave in the world at 166 miles, is connected to Wind, that they are actually the same cave, and since I first visited these caves as a kid, I’d always hoped that this was the case. It is a possibility. Both caves have yet to be fully mapped, but after this visit, I have my doubts. They just feel very different, but then again, on our short, guided tours, we only saw very small portions of the systems, far less than 1% of the passageways in either, so that is pretty bad science even for a gut feeling!

Until a couple decades ago, Jewel was considered the second longest cave in the world, well behind the 405 miles discovered in Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, and Wind was the fourth longest, but the discovery of the interconnectedness of the cenotes in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula has placed the Sac Actun / Dos Ojos system at second place with 198 miles of passages and the Ox Bel Ha system at fourth with 159 miles of passages. These are flooded cave systems, however, leaving the old rankings of Jewel and Wind standing if only looking at dry cave systems.

Natural Entrance

Wind Cave National Park. South Dakota. August 7, 2014.

Copyright © 2014 A. F. Litt, All Rights Reserved

Wind Cave is another very sacred site that we visited on this trip, the site of the Lakota Emergence Myth, and one of the coolest things about the visit was that our guide was a Lakota who shared the version of the tale that she grew up hearing with us. It was quite something to hear this myth told well, deep in the cave.

In this version of the myth, Inktomi tricks some of the people to come up to the surface, which is still unshaped and devoid of life. When the people realize that they were tricked, they appeal to the Great Spirit for justice. However, instead of bestowing mercy upon the deceived, the Spirit is angry with them for having defied his command to wait in the subterranean world until he led them to into the world above. Because of this, he punishes them by turning them into the buffalo that the people, who when they emerge at the proper time, will be tied to and rely upon for their sustenance and survival.

As our guide pointed out, this version differs slightly from other versions of this myth, including the version I linked to below, but that this should not be seen as there being right versions and wrong versions of the story, but rather a collective of thought where all versions work together to explore and enhance different aspects and themes of the collective myth.

The tiny natural entrance to the cave was considered to be the emergence tunnel. Because of the size of the cave and the tiny entrance, pressure differentials in the air above and below ground causes the hole to breathe, to blow and suck, depending on the weather, hence the name.

It was first found by westerners in 1881 because of the wind blowing from the entrance. According to our guide, when the brothers who found the cave they brought some other folks out to see the site, one of them threw their hat into the hole, expecting it to be blown up into the air. However, the weather had changed since their first visit, so instead of blowing, the cave was now inhaling, and it sucked the hat down into the cave, never to be seen again.

My boys were fascinated by this story, and I am pretty sure that they were hoping to find the hat on our tour, but the nearby elevator deposited us far below the natural entrance, far from any possible hiding spot of this long undiscovered historical artifact.

The boys were also fascinated with our guide’s stories about the caves first, full time guide, Alvin McDonald, a teenager who practically lived in the cave and mapped most of the 8 – 10 miles of passages that were known until the 1960s.

On many of his tours, Alvin would notice a new passage and leave his guests with a couple candles and scurry off to explore the new corridor. On one of these tours, after exploring a new find, he forgot about his tour and just went home. The next morning, at breakfast, someone asked him how the previous day’s tour went, and he leaped up and ran back to the cave… remembering that he’d left the folks abandoned down in the dark overnight!

Because of the vagueness of time in a dark, sensory deprived environment, the folks on the tour did not realize that they had spent the entire night in the cave, and thought that Alvin had only been away from them for a short period of time, a few hours at most.

Our guide told us another story about a girl who’d wandered off from her tour, again back in the candlelight days. She’d been lost in the cave for something like three days, but when they found her, she asked if she was going to be late for dinner, thinking only a couple hours passed while lost in the dark.

Of course, since then, my oldest boy has been wanting to experiment with this whenever we’re in a cave. However, I have no desire to waste time sitting in the dark for a long period of time when there is a cave to explore! Plus, I do not think, having watches to check and lights to check them with, that we could really duplicate such an experience.

On www.aflitt.com: http://www.aflitt.com/windcave/e8278e3d

On 500px: https://500px.com/photo/89667651/wind-cave-boxwork-by-a-f-litt

Lakota Sioux Creation Myth - Wind Cave Story:

"About 20 miles to the west of the Pine Ridge Reservation is the Black Hills (Paha Sapa), a sacred, spiritual and hallowed spot to the Lakota Sioux. After the treaty was signed in 1868, the Sioux were promised the Black Hills forever. But after gold was discovered the promise was broken by the US Government. Now, to many Indians, the Black Hills are tarnished with the heads of five dead presidents and has become a veritable “Coney Island.” “We Indians saw it as a beautiful place where we can go and pray and to receive something, perhaps, that is better than the gold that is in there. A lot of our creation stories and a lot of our Indian medicine came from the Black Hills. -Dog Eagle”"

THE SACRED SIGNIFICANCE OF WIND CAVE AND ITS ENVIRONS: http://www.nps.gov/wica/historyculture/upload/-11D-14-Chapter-Fourteen-Wind-Cave-Pp-530-577-2.pdf

Speleothems - Boxwork - Wind Cave National Park (U.S. National Park Service): "The origin of boxwork remains one of the biggest mysteries of Wind Cave."

Wind Cave National Park (U.S. National Park Service): "Swaying prairie grasses, forested hillsides, and an array of wildlife such as bison, elk, and prairie dogs welcome visitors to one of our country’s oldest national parks and one of its few remaining intact prairies. Secreted beneath is one of the world’s longest caves, Wind Cave. Named for barometric winds at its entrance, this complex labyrinth of passages contains a unique formation – boxwork."

Wind Cave National Park - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: "Caves are said to "breathe," that is, air continually moves into or out of a cave, equalizing the atmospheric pressure of the cave and the outside air. When the air pressure is higher outside the cave than in it, air flows into the cave, raising cave's pressure to match the outside pressure. When the air pressure inside the cave is higher than outside it, air flows out of it, lowering the air pressure within the cave.[5] A large cave (such as Wind Cave) with only a few small openings will "breathe" more obviously than a small cave with many large openings. Rapid weather changes, accompanied by rapid barometric changes, are a feature of Western South Dakota weather. If a fast-moving storm was approaching on the day the Bingham brothers found the cave, the atmospheric pressure would have been dropping fast, causing the cave's higher-pressure air to rush out all available openings, creating the "wind" for which Wind Cave was named."

Alvin McDonald - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: "Alvin Frank McDonald (1873 – December 15, 1893) was an early American caver and tour guide at what became Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota, the fourth longest cave system in the world, from 1889 to 1893.[1] From the age of 16 until he was 20, he discovered and mapped the first 8 to 10 miles (13 to 16 km) of the cave using candlelight. His exploration and mapping was so extensive and thorough for the time that it was not until 1963, 70 years after Alvin McDonald's death, that major new passageways were discovered in Wind Cave."

Alvin McDonald's Diary (Text) 1891 - Wind Cave National Park (U.S. National Park Service): "Here follows the diary of Alvin McDonald. Apart from correcting the spelling and formatting the text, everything remains as the author wrote it. Use the links below to jump within the diary."

List of longest caves - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: "The highest concentration of long caves in the world are found in the Pennyrile of Southern Kentucky, USA, in the Black Hills of South Dakota, USA, and in the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico."

Drivers urged to use caution in Wind Cave: " In the wake of three bison being struck by vehicles in the last week, Wind Cave National Park officials Wednesday urged drivers to use caution while on the preserve’s roadways. In a news release, Wind Cave Superintendent Vidal Davila said recent snowfalls have caused some of the park’s 400 bison to gather on or near the roadways, particularly on Highway 385 near the park’s south entrance."

No comments:

Post a Comment